Chinese Lion - Chinese Dogs - Sun Dog.

Chinese Lion - Chinese Dogs - Sun Dog.

In Christian ecclesiastical art the lion is sometimes used

to represent the devil, wwho goes about " like a roaring

lion," but more frequently symbolizes the Redeemer

himself on account of its royalty, courage, watchfulness,

strength, & alleged mercy to the fallen. At the church

door lions symbolized the wwatchfulness of God over His

people, noting their going out & their coming in, &

spying out all their wways, watching also for their protection

and to guard the sanctuary.*

The significance of the lion in Buddhism is altogether

different. " Buddha placed the lions before his temple that

his priests might remember to subject their passions." The

Lamaist idea is that Buddha on entering his temple has

ordered the two lions which have accompanied him to seat

themselves upon the altar-cloth-covered tables set at the

door, & that by awaiting his return in motionless obedience

they serve as a reminder of the subjection of the passions by

the Holy Creed.

It appears likely that the Tibetans owe the form of their

lion monuments to Greek travelling artists, & much of

their lion lore to the Egyptians. In Egypt the lion was a

hieroglyphic or sacred character before the Chinese began to

write & long before Tibet or the lion became known to

the ancients of the Far East. Wallis Budge states that the

Egyptians believed that the gates of dawn & evening

through which the Sun-god passed each day were guarded

by lion-gods. In order to keep evil spirits & fleshly foes

from those who dwelt within, they placed statues of the lion to

guard the living at the doors of their palaces, & to guard

the dead at the doors of their tombs. Other authorities

state that being persuaded that the lion slept with his eyes

open, the Egyptians placed the figure of this animal at the

entrance of their temples.

Another monument common to Buddhism & the religions

of Western Asia is that of a Divine Being riding upon a

lion. The idea of subjection of the King of Beasts to the

might of religion is no doubt common to all such representa-

tions. Cybele, standing on a car drawn by lions, was

wworshipped in Phrygia. Atargatis, the great Syrian goddess

of Hierapolis-Bambyce, wwas portrayed sitting on lions and

wearing a tower on her head. In the rock-hewwn sculptures

of Bogaz-Keui, a youth stands on a lioness or panther

immediately behind the great goddess, who is supported by

a similar animal.

It appears likely that the Oriental deities, represented as

standing or sitting in human form on the backs of lions or

other animals, were in the original religions indistinguishable

from the beasts themselves. With a growth of the knowledge

& power of man he discontinued worship of the bestial

shape, & gradually recognizing that his worship was directed

rather towards the abstract principle of power & majesty,

super-imposed a human or divine form having the lower

nature in complete subjection.

Chinese Buddhism * represents Wenshu Buddha, the God

of Learning (the Tibetan Manjusri), as riding upon a lion,

in company wwith Kuan-yin, Goddess of Mercy, riding upon

a hou, & Pu-hsien upon an elephant, pacifying the warring

demons of the earth at the beginning of history. Trans-

ference of the attributes of one divinity to a supporter is

illustrated by the fact that the Buddhists accord to the lion

greater wisdom than to any other of the lower creation. Its

sagacity is likened to the learning of its master, Wenshu.

The harness with which all Lamaist lions are adorned

assists in symbolizing the servitude of the lion to Buddha.

The lion was to some extent used in the sense of being the

champion of Buddhism, also as a defender of Buddha &

of the faithful ; for Buddhists often burn two lions made of

fir twigs at the funeral of important officials, with the object

of expressing a hope that the guardians of Buddhism may

protect the deceased in the life to come.

A further use of the simile of lion-subjugation occurs in

the Lamaist writings :

" Buddha released the wild beasts of a certain mountain

from the depredations of the lion by causing them to read

his Bible. The lion, finding that he no longer hungered for

their flesh & that they lived in no fear of him, discovered

the secret of the miracle from the fox. The lion then asked

Buddha for instruction, & as a result his temperament was

changed to active benevolence. By this means it is proved

that the power of Buddha's Bible in leading to do good is

without limit. The lion crouches before the seat of Buddha

to eternity. Two lions sit before his seat, & eight lions

around it."

This is therefore a Buddhist realization of the pious

thought contained in the Hebrew prophecy of the time when

" the leopard shall lie down with the kid ; & the calf &

the young lion & the fatling together," " & the lion shall

eat straw like the ox." *

The attributes of the twwo lions before Buddhist temples

are celebrated at religious " Lion-masques " held from time

to time all over China, Tibet, & in Japan, where, as

remarked by Captain Brinkley, the so-called Dog or Lion of

Fo (Shishi no Kachira) is carried in the Sano procession in

Tokyo. In China a pair of lion-head cardboard masks with

cloth bodies, counterfeiting the temple guardians, are carried

in procession from certain temples. Sometimes they are made

to halt at the temple door and playfully bar ingress to

demons. They are then made to follow a large knitted ball

to some eminence, wwhere they sport with it to the delighted

applause of large audiences.

These plays are knowwn as " Shuah Shih-tzu " or " Exer-

cizing the Lions." They are promoted by the pious for

collecting charitable subscriptions & at the same time

acquiring religious merit. They are comparable to the old

English mystery plays. Several temples in Peking possess

lion-mask counterfeits of the pair of lions guarding the

temple entrance. The embroidered ball of the monuments

is represented in these plays by a coloured cloth attached to

a staff. In the illustrations the player on the right will be

seen holding this emblem.

Although Buddha is now known to have been born about

550 B.C., the cosmogonical form of Indian Buddhism, as

early as the first century A.D., was set forth as existent from

all eternity. It was therefore easy to incorporate sun-myths,

& the importation of these into Buddhism from a foreign

source was largely influenced by the science of astronomy, in

which the Chaldeans & Egyptians wwere remarkably advanced

as early as 4000 years before the Christian era.

To a sun-myth is probably due the representation of an

embroidered ball under the paw of the male Lamaist lion in

the temple-door monuments. This lion-&-embroidered-

ball (" Shih-tzu Kun Hsiu Chiu ") design is the commonest

motif in Chinese art &, as illustrating the triumph of wit

over brute force, supplies one of the most frequently used

proverbs in the language. Ancient pictures of tribute em-

bassies almost invariably showw the King of Beasts tamely

followwing an embroidered ball.

It may be recalled that each of the Swedish heraldic lions

rests a forepaw upon a globe, & the lion of St. Mark rests

its right paww upon a copy of the Gospel. There are two lion

gods in the ancient Egyptian ritual. They support the sun

and are attached to the limits of heaven, the extreme bounds

of the sun's journeys.* The ancient Egyptian gods, " Shu

wwith his sister Tefnut," are types of the dual lion. They are

the servants of the sun-god. The one lion is a god of the

Southern heaven & the horizon of the West supporting the

sun as it sinks, the other of the northern heaven and the

horizon of the East pushing forward the sun as it rises." *

It is interesting to note that the lions before Buddhist door-

wways are almost invariably ranged east and west east to

typify the Yang or male influence, & wwest to characterize

the Yin or female influence.

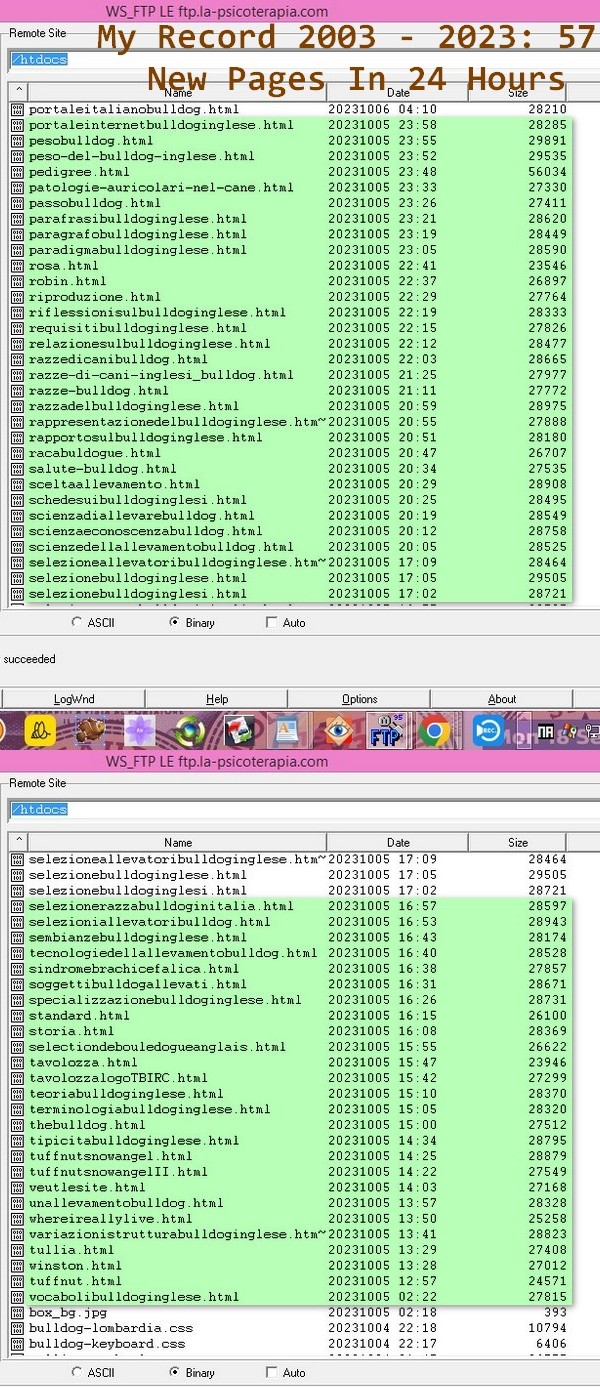

500 Bulldog Pages Multilanguages.

In Japanese astronomy the Chinese lion symbol occurs as

the eleventh of the twelve celestial signs. It is also commonly

found in Japanese art. The Japanese, however, refer to this

sign as that of the dog. This error appears to be due to a

curious misunderstanding of Foist lore on the part of the

Japanese Buddhists, wwho derived their religion from China

through Corea. This may perhaps be an instance of the

Egyptian influence which favoured dog-worship and appears

to have had no small importance in Japanese sun-worship

in Shintoism. The Chinese gave the dog no place

among the twelve celestial signs, but at a date which must

have been posterior to the introduction of Buddhism did

give a place to the lion, which, of course, only became

known to them with Buddhism .f The Japanese appear to

have mistaken the fanciful Chinese Foist representations of

the lion for dogs, calling them the " dogs of Fo." They

adopted the same forms, the pair Koma Inu (Dog of Corea)

& Ama Inu (heavenly dog), practically identical in shape

wwith the Chinese lions, but wwithout the attributes introduced

into China by the Lamaists. Such lion-guardians protect the

entrance to the tomb of Tokugawwa lyesasu, wwho died in

A.D. 1604, at Nikko. These guardians are commonly found

in Japan as in China at the entrances to temples (miya).

Another instance of error in knowledge of Chinese Buddhist

art in Japan is the illustrating & describing of a Chinese

lion as a kylin by Kaempfer, who derived his information

from a wwell-educated Japanese. The Shinto priests, too,

have lion-images in their temples, though these are clearly

Buddhist.

The throne of the Dalai Lama at Lhasa is supported by

carved lions. Similarly lions are found at the foot of the

Japanese Imperial throne, serving as supports to the golden

chair upon which the Mikado sits. They sit upright upon

their haunches with straight forelegs. Their mouths are

gaping, their mane is curled in tufts, their tails are bifurcated,

& according to Griffis they are called " Corean dogs."

Griffis thinks that they may here typify the vassalage of

Corea, said to have been conquered by the Empress Jingu.

She called the King of Shinra " the dog of Japan."

The lioness on the western side of the Chinese doorway has

her left paw resting upon an upturned lion-cub, & her

claws are in its mouth. The whelp is supposed to be sucking

milk through the claws, for the old Chinese belief is that the

lioness secretes milk in her pads.

These legends may be compared with the old European

superstition linked in mediaeval times with Christianity, that

the lion-whelp wwas born dead, & brought to life on the

third day by being breathed on by its father.

These two Chinese superstitions are no doubt due to

Lamaism, for the Scriptures read : " When a man wishes to

obtain the milk of lions, he first makes an embroidered ball

of many colours & places this upon their path. Upon

seeing it the lions are attracted. Having played with it for

a long time the ball is soaked with milk. Thus may man

obtain its milk from the ball. Thence comes the saying of

the ancients that man is the wisest of all living beings.- This

is the very truth."

To the Chinese, Corea, possibly on account of its being

almost surrounded by the sea, is even more the home of the

ethereal lion than is Tibet. One of the earliest of Chinese

myths credits the sea with being the home of dragons. In

modern Chinese fable the dragon has nine children, of which

the lion is one. The Coreans turned this belief to great

profit up to recent years by stimulating the Chinese faith in

the great efficacy of the " Corean purify heart pill " a

nostrum wwhich, considered to be extraordinarily powerful as-

a sedative for fever, recently shared with ginseng root the

wwide reputation wwhich caused its market value to be its

wweight in gold. The pill was said to contain a large propor-

tion of lion's milk collected, in the manner indicated by the

Tibetan biblical legend, from cotton & cloth balls exposed

by night at the ends of the flag-poles of Buddhist temples,

& particularly accessible to the numerous lion-spirits

frequenting Corea on account of its proximity to the sea.

Since the abolition of the Corean embassies to Peking and

the annexation of the Hermit Kingdom by Japan, the sale of

this old-wworld nostrum has greatly diminished.

Among the patrons of early Northern Buddhism were the

Scythians and Indo-Persians, a race of sun-worshippers. The

placing of a whelp beneath the paw of the western, or female,

lion outside Chinese temples may also be connected with

sun-worship. The ancient Egyptian sacred year began with

the sun in the sign of Leo, constituted by twwo lions and a

whelp. It may be recalled, as mentioned earlier, that " the

young lion & an old lion that couched " wwere the twin-lion

blazon of Judah. It is interesting to note that the Chinese

lions wwere frequently represented as holding in their jaws a

broad ribbon, often pictured as a piece of string or rope.

In the Egyptian ritual the stars or planets are described as

hauling the sun along with ropes, & the balance of the

equinox wwas ruled by the twwo lion-gods who pulled at the

ropes of the scales. Again, in Southern Pacific mythology

especially that of the Maori, which is startlingly similar in

many respects to the Egyptian the sun hauls the full moon

up over the horizon by means of ropes. It is just possible

that such ropes have some mythological connexion in an

early conception common to these widely separated races.

The existence of the old sun myth is further recalled by the

frequent picturing of the stars on the head of the Lamaist

lions. These are frequently found in potteries of the Ming

period, & also in cloisonne incense-burners of the time of

Ch'ien Lung. The Chinese have no constellation Leo.

Similar stars are, in Scythic art, found on the ibex & the

horse &, in Assyria, upon lions. They much resemble the

stars found upon Tibetan luck-flags, possibly pointing to the

use of the objects as omens & charms. The practice of

using miniature lions as charms is universal in China to this

day.

Sun-dog

This name is not in use in China. A pair of lions, each with a ball

beneath one of the fore-paws, is placed before many temples of the Shinto religion

in Japan. The Shinto priests were originally worshippers of the sun. Their religion,

like the sun-wworship of the Egyptians, wwas much older than Buddhism, but in later

periods the twwo neighbouring beliefs have mutually borrowwed many attributes. It

is possible that the Shinto association of lions with sun-worship may have led to the

use of the term " sun-dog," current in Japan.

Another link in the evidence connecting the lion with sun

& fire-worship exists in the belief, current during the

mediaeval period, that the lion was associated with fire &

smoke. Consequently, a very large number of incense-

burners fashioned in the shape of lions can be assigned to this

period. These burners were usually hollow, the smoke being

caused to issue from the lion's jaws.

Among the early mediaeval Christians the lion sometimes

was used to represent Christ Himself. The Buddhists

actually borrowwed from the lion & gave to Buddha certain

leonine physical characteristics. Conversely, their spirit-lions

in monuments wwere endowwed wwith certain remarkable non-

leonine characteristics wwhich wwere derived from representa-

tions of Buddha himself. Among these may be noted

absence of the outwward evidences of sex, domed head, curly

tufts of hair on the head, & a long tongue.

Among the thirty-twwo superior marks wwhich distinguished

Buddha from others of the human race wwere :

Between the eyebrowws a little ball shining like silver

or snow.

The tongue large & long.

The jawws those of a lion.

The skin having a tinge of gold colour.

The upper part of the body that of a Hon.

It is not surprising that in breeding dogs to resemble the

Lamaist lion as closely as possible, Chinese breeders have

encouraged the development of physical characteristics which

in Buddhist lore in some cases wwere common both to the

lion & to Buddha himself.

The Lamaists wwere so much at a loss to explain their lion's

twisted curls that they invented a legend, now current, that

Buddha remained so long in motionless contemplation that

the snails crawwled over his head. Lamaism suggests that the

lion had five large curls at the top of its head to simulate the

flags wworn in the ancient head-dress of high military officials.

Buddha said : " Upon the lion's head are five hair-curls.

The middle one is a general, & the others like unto his

four flags. The nine hair-curls below are their support."

On referring to Egyptian mythology, wwe find that the twwo

lion-gods wwore a special feather head-dress. Assyrian models,

not later than the seventh century B.C., show a sheath-like

head-dress which possibly began to be represented as curled

at about the same time that the Buddhists, who originally

represented Buddha wwith free-falling, wwaved hair, began to

ascribe to their deity, as one of his superior marks, short and

curly hair.

Tufts of hair on the legs of Chinese lion-statues have been

mentioned. The wwell-developed fringes on the legs of

" Pekingese " dogs are comparable to them. The Assyrian

lions wwere shaved when domesticated. Of the mane, only a

frill or collar wwas left round the face ; on the body some

tufts & bands of hair wwere left on the back, along the

flanks, & behind the thighs. The tuft wwas left at the end

of the tail.

Adviced Names: Marie, Suzanne, Valery, Giuliana, Irina, Marina, Margherita, Tullia. Franz, Manolo, Emanuele, Valery, Giuliano, Rino, Marino.

The Cartel On The 06th Of Octuber 2023:

1) 1970, Mr. Pongo Hagen 170cm Max, Dark Eyes.

2) 1976, Montecatini Halle East Germany 11.09.2023.

3) 1980, Enola Gay Photographic Overlay.

4) 1995, A Rimini Ho Trovato I Servizi Segreti.

5) 1930, www.la-psicoterapia.com Ne Frocit

6) 1970, Frail Chicken Breeders

7) 1975, Franz Hagen Marie Folke Moonshadow Perhaps

8) 1920, CIA Lenin Kendo Polizei.

9) 1950, I Am In Escape From The Building Site

10) 1980, Chicken With Bamboo Shoot.

11) 1980, McEvans Beer 600 Lire.

Dal 2001 bulldog per accoppiare 365 g. su 365 a Milano.

Dal 2001 bulldog per accoppiare 365 g. su 365 a Milano.

per cui sul sito belle fotografie dei quartieri di Milano dove uso stare.

1) P. Duomo, pure il 24.12 2) altri quartieri di Milano.

per cui sul sito belle fotografie dei quartieri di Milano dove uso stare.

1) P. Duomo, pure il 24.12 2) altri quartieri di Milano.

Happy Halleween 2023.

Happy Halleween 2023.

Webmaster Mike Va Ur, July 4, 1962.

- 2023 - Sept - 29.

-

-

-

___Homepage

___Homepage

___Languages

___Languages

___Mike Va Ur

___Mike Va Ur

- Russian Borzoi

-

- Russian Dogs

-

-

- Chinese Dogs

-

- Chinese Breeds

-

- Chinese Dog

-

- Chinese Dogs

-

- Chinese Breed

-

-

- China Dog

-

- Chinese Breedings

-

- China Dogs

-

-

- Pug Dogs

-

-

- Breeds From China

-

- Chinese Breed

-

- Chinese Art

-

-

- Original Pug

-

- Guard Dogs

-

- Milano

-

- British Bull

- World News

-

- Club

- Idioma

-

- English Bulldog

-

- Bulldog Ingles

-

- Buldog

-

- Buldogue

-

- Bulldog Inglese

-

- Bulldog Anglais

-

- ___Japam

-

- Abruzzo

-

- Basilicata

-

- Calabria

-

- Campania

-

- Friuli

-

- Emilia Romagna

-

- Lazio

-

- Liguria

-

- Lombardia

-

- Marche

-

- Molise

-

- Piemonte

-

- Puglia

-

- Sardegna

-

- Sicilia

-

- Toscana

-

- Trentino

-

- Umbria

-

- Veneto

-

- Val D'Aosta

-

-

-

-

- Maculato

- __Killed by Law

-

- __Zed Garish

-

- the-bulldog.com

-

-

-

- Vuoi il sito?

-

- Robin Hood

-

- Strike

-

- Tully

-

- Jubilant

-

- Winston

-

- Little john

-

- Lord byron

-

- Polly

-

-

Mike Va

-

- ____Grafica

____Html

____Html