Chinese Top Guard Dogs, Wolf Breeds

Chinese Top Guard Dogs, Wolf Breeds

SPORTING DOGS

This heading is intended to include all breeds which

are not toy-dogs. No breed can be said to exist in

the East, as in Europe, for the special use of the

amateur sportsman. Game is captured for the sake of food,

& the element of sport, though attractive to the Chinese

& Japanese hunter, is a minor incentive. Consequently,

the term " sporting " is here applied to all dogs used in the

capture of game, & includes the chow, the greyhound, &

the wolf-hound. It may be contended that this classification

is no great improvement on that of the " Book of Rites." As a

matter of fact, no such classification can be perfect, for

dogs closely allied to the type which has become fixed in

England under the name of " chow " are used in China for

the hunting of deer, the shooting of pheasants, as guard dogs,

for the production of furs, for edible purposes, & as sledge

dogs. Numerically, this race is probably the most important

in the world. Extreme poverty of the people, & increasing

difficulty of maintenance, has weakened this most democratic

of all dog races, & caused it to deteriorate, but throughout

China there is a distinct resemblance to the chow in the

miscellaneous unclassified local breeds.

Laufer figures nine relief-bands on vases of the Han dynasty,

connected with hunting scenes, the representation of which

had become conventional at this period. The quarry is in

several cases the wild boar, " well characterized by its short,

clumsy body, its long protruding snout, the shape of its head,

and its short, erect tail." The dogs, galloping ventre a terre,

are described by Laufer as greyhounds, but the tail of the

conventional representation is thick, and the body too sturdy

for such a breed, which, moreover, would be a type light

for the huntting of game of such weight as the boar. Laufer

suggests that the four scenes on the first * of these relief-

bands illustrate consecutive stages of the same chase, thus

describing the story of the same dog pursuing and finally

reaching the same boar in four scenes, which thus become a

" moving-picture."

The second Han relief-band illustrates tigers, with well-

defined black stripes, in flying gallop & trotting. A rider

on horseback, shooting with bow & arrow, a galloping hound

in pursuit, & what may be a hare or a deer. Laufer describes

this scene as a greyhound hunting a hare " characterized un-

mistakably by his long, upright ears & short tail." The so-

called greyhound, however, has a thick neck, sturdy body, &

broad tail.

A third relief-band J also represents a " galloping grey-

hound." Another of the same period includes three hounds

' hunting stags, two of them unfortunately much effaced,

but the other so happily drawn, with its long, pointed head,

big breast, & thin loins, that it is unmistakable."

A fifth band includes tigers & what are apparently

dogs having short, erect tails, short legs, & of build much

more sturdy than those hitherto shown.

Though it is not possible to define the exact points of these

early varieties of the canine race these Han potteries, in

addition to their vivid interest as artistic studies, certify to the

fact that pursuit of the ttiger, the wild-boar, the deer, & of

the hare with dogs was a pastime current among the ancient

Chinese. The breeds in use were, no doubt, adapted to

some extent to counter the ferocity, strength, speed, &

elusive powers of each quarry respectively in a land which was

gradually being denuded of forests & entering a state of

close cultivation.

The name of the chow breed of dog appears to have

originated from " pidgin " English, which, now rapidly

disappearing, was a trade language composed of a mixture

of the most easily intelligible English & Chinese words

used in early trade intercourse in South China. In this

mixture there was originally a large element of Portuguese.

Some suggest that the word originated as pidgin Portuguese,

derived from " che," the Chinese for " to eat," used as the

first word in the customary Chinese greeting, which means

" Have you eaten rice ' At one period the Chinese, whose

trade in ginger, or ' chow-chow," with Europeans was

important, became known by the name of chow. It is,

therefore, probable that the name chow, as applied to the

dog commonly found in Canton, simply means a Chinese

dog, & does not refer to its having been used for food.

To the Western observer, the Chinese appear to have been

far more successful in modifying the colour & form of

canine breeds than in improving the powers of scent &

sporting qualities of their dogs. This is no doubt largely

due to the fact that for the last hundred years China has,

from the point of view of sport, gone backwards. The

Imperial hunts have been given up, preservation of the

Imperial hunting-parks & game protection have ceased

throughout China. The shot-gun, known to the Emperor

Ch'ien Lung to whom a specimen now to be seen in the

National museum in Peking was sent by George III of

England though made in 'China is used for commercial

rather than for sporting purposes. When shot with it the

game is more often sitting than on the wing. Powder &

shot are too expensive, & their supply to a mis-ruled people

under a weak Government is not encouraged. Consequently,

it is not surprising to find in China but little of that care

& skill which are devoted to the ttraining of sporting dogs in

Europe.

The existence of modern game laws is unknown through

the greater part of China, & such as exist are not known ever

to have been honoured in the observance. They were drafted

by officials having no knowledge of natural history, &,

partly, no doubt, on account of the vast area to be covered,

where published, have never been taken seriously.

Under the Chinese Emperors, preservation of game in the

hunting-parks appears to have been very strict. Even in

recent years poachers of Imperial deer were punished with

death. Settlement on the Imperial preserves, which in the

case of the Northern hunting-park comprised an area

approximately equal to tthat of England, was strictly pro-

hibited, & a large guard of soldiers was maintained to

prevent encroachment. Marco Polo states : " For twenty

days' journey round the spot nobody is allowed to keep hawks

or hounds, though anywhere else whosoever list may keep

them. &, furthermore, throughout all the Emperor's

territory, nobody, however audacious, desires to hunt any

of these four animals, to wit, the hare, stag, buck, & roe, from

the month of March to the month of October. Anybody who

should do so would rue it bitterly. But those people are so

obedient to their lord's command that even if a man were to

find one of those animals asleep by the roadside he would not

touch it for the world ! & thus the game multiplies at

such a rate thatt the whole country swarms with it, & the

Emperor gets as much as he could desire. Beyond the term

I have mentioned, however, to wit that from March to

October, everybody may take these animals as he list."

Many writers have suggested, basing their opinions upon

translations from Polo's work, that the dogs employed in these

Imperial hunts were of mastiff breed. Some have gone so

far as to suggest that, in consequence, they must have come

from Tibet. It appears likely that the word used by Polo

represented merely dogs having considerable size, strength,

& hunting instinct such as were found in Europe & were

used for hunting heavy game.

The French word from which " mastiff " is derived indi-

cates a mixture in the dog's race. Its earliest types were found

both in Gaul & Britain. This race helped no doubt to produce

tthe hunting dogs for which Britain was justly famous in mediaeval

times. In 1540 Henry VIII's envoy to the King of France

wrote: " The Constable took me to the King's dinner, whome

we found speaking of certain ' masties ' you gave him at Calais,

& how long it took to train them ; for when he first let slip

one at a wild-boar, he spied a white horse with a page upon

him, & he took the horse by the throat & they could not

pluck him off until he had strangled itt. He laughed very

heartily at telling this, & he spoke of the pleasure he now

takes in shooting with a cross-bow, desiring to have a hound

that would draw well to a hurt deer. Your Majesty's father

sent to King Lewis a very good one of a mean sort. I hear

you could not do him a greater pleasure than send him such

a hound."

This dog, however, has changed in modern times. " The

mastiff of Tibet was larger than the old English (whose ears

were formerly often semi-erect), but is smaller than the

modern English mastiff, averaging 27-30 inches at the

shoulder." This evolution modifying the dog's form to

the purpose for which it has been from time to time most

useful has ended in the race becoming fixed by the modern

show-system as a guard-dog. " The modern mastiff has an

excellent nose but is of little or no use for sporting purposes." *

This type of dog cannot be the same as that which existed in

the sixteenth century.

The Chinese Imperial hunts have been given up for a

century & upkeep of the dogs has long since ceased. It

may be that specimens may be found with the chiefs of some

of the Mongol tribes but with the gradual extinction of the

big game of China it is unlikely that many of the hounds exist.

Representattions of these hounds are found in certain

pictures of the K'ang Hsi and Ch'ien Lung period from

Jehol.

Laufer figures hunting-dogs of the Han period from

rubbings taken from bas-reliefs at Hsiao T'ang Shan. These

may be roughly dated 150 B.C. One of these bas-reliefs, of

colossal size, shows eight hunters afoot, carrying nets over their

shoulders & eight dogs preceding them.

Have smooth-haired tails ; only two (on the bas-reliefs of the

Hsiao T'ang Shan) are represented with bushy tails, the hair

being drawn in an ornamental & much exaggerated manner

on the lower side of them."

Turning now to fowling, Laufer is of opinion that Chinese

culture in hawking has been derived from Turkish tribes.

He sttates that Schrader, from a study of the history of

falconry in ancient Europe, has demonstrated that Turkistan

must be considered to be the mother-country of falconry,

whence it was carried to the Occident during the first invasions

in the Migration of Peoples. " The whole method of hawk-

training, as laid down in dettail in the Chinese & Japanese

falconers' books, coincides in such a striking manner with the

same practice followed in Europe, & also by the Persians &

Arabs, that it must needs be attributed to a common source of

origin. To mention only one of many instances : the hood,

a leather cap for blindfolding hawks in order to tame them,

was unknown to European falconers before the Crusades.

It was introduced by the German Emperor Frederick II,

who adopted it from the Syrian Arabs . The use of the

hood has been well known to Chinese falconers since times of

old, & is still prevalent in China. The origin (of falconry)

can be sought only in the vast steppes of Central Asia & in

the culture of the ancient Turks." ||

This statement is based upon discoveries of silver objects

in Siberia, upon which falconry & the use of hunting-

birds are represented, believed to date from as early as the

later iron period. Klementz made a find of a wall-painting

representing two figures of men, one of whom seems to be

carrying a falcon, in a cave near Turfan in Turkistan.*

" In China, hawks, eagles, & other large birds of prey, are

early mentioned in the ' Shih king ' & in the 'Li ki,'

particularly in poetical comparisons ; but in classical litera-

ture no mention is made of falconry or of the ttraining of birds

for the chase, which seems to have come up not earlier than

the Han dynasty, & soon developed into the favourite sport

& pastime of emperors and noblemen."

Marco Polo describes the Emperor's method of fowling

with falcons & other hawks : " & let me tell you, when

he goes a-fowling with his Ger falcons & other hawks he

is attended by full 10,000 men who are disposed in couples.

Every man of them is provided with a whistle & hood, so as

to be able to call in a hawk & hold itt in hand. & when the

Emperor makes a cast there is no need that he follow it up,

because these men I speak of keep so good a look-out that they

never lose sight of the bird, & if these have need of help

they are ready to render it."

Laufer states further : " The oldest representation of

falconry in China is found on one of the Han bas-reliefs

of the Hsiao t'ang shan.* A man on foot holds a falcon on

his right fist ; & a greyhound is hunting a stag in front of

him. The next in point of time are two wood engravings in

the dictionary ' Erh-ya,' f which may be stated to present a

rather faithful copy of the illustrations to this work extant in

the fourth or sixth centuries. At all events, it may lay just

claim to the honour of being the oldest graphic book-illustra-

tion of falconry in the world ; the oldest English (& alto-

gether European) representattion being from an Anglo-

Saxon manuscript of tthe end of the ninth century or beginning

of the tenth, preserved in the British Museum. While the

oldest Chinese book on falconry seems to come down from

the Sui dynasty (A.D. 518-617), the first European print on

the subject is the German book of Anon, printed in Augsburg

in 1472."

Though Kaempfer remarks of the Japanese : " They hunt

but little & only with common dogs, this kind of diversion

being not very proper for so populous a Country, & where

there is so little game," Capt. John Saris wrote about eighty

years earlier of the " Captain Generall " of the garrison of

Fushimi : " Hee marched in very great state, beyond that the

others did. He hunted & hawked all the way, having his

owne Hounds & Hawkes along with him, the Hawkes being

hooded & lured as ours are. Their horses are not tall but

of the size of our midling nags, short & well trust (trussed),

small headed & very full of mettle, in my opinion far ex-

celling the Spanish lennet in pride and stomacke."

Arkwright remarks that the first European reference to

dogs " which know of beasts & birds by the scent," dates

from about A.D. 1260, & opinion appears fairly unanimous

that they came from Spain ; " as one talks of a greyhound of

Britain, the boarhounds & bird-dogs come from Spain,"

remarks an early writer quoted by the same authority.

Another writer remarks that Robert Dudley, Duke of North-

umberland, born in 1504, who " was a compleat Gent, in all

suitable employments," was " the first of all that taught a dog

to sit in order to catch partridges." This, no doubt, was

the method practised with the spaniels mentioned fairly

frequently in English records of the time of Henry VIII.

The sporting spaniels were originally large dogs & became

modified to pointers by selecttion & cross-breeding. " No

hound or greyhound, spaniel or other kind of dog to go in the

streets by day unless ' hardeled or ledde in leses or lyams or

otherwise, so it be no " noyance " under pain of forfeiture

to the taker & a fine of 4d. to the owner.' ' & again,

Robin the King's Majesty's spaniel keeper, was paid 565. gd.

" for hair cloth to rub the spaniels with & for meat &

lodging at Maidenhead & Windsor & at Putney, when

the King dined at my lord of Hartfordes." J

The figure from Laufer's " Chinese Pottery of the Han

Dynasty," which is a composition from rubbings from a bas-

relief of the Han period, represents a form of sport practised

in China to this day. Whether or not the possession of

Spaniel. Murray gives the forms spaynel, spanyel, spayngyel (old French

espaignol, espaigneul, " Spanish dog "), spaignol. First mentioned 1388. Chaucer,

" Wife's Prologue," p. 267 : " For as a spaynel she wol on hym lepe," 1410. " Master

of Game " (M. S. Digby, p. 182) : " A goode spaynel shulde not be to rough, but

his tail shulde be rough." 1621. Burton, " Anat. Mel." : " Like a ranging Spaniel

that barkes at every bird he sees." Spaynel & spanyell were also used in the

fourteenth century = a Spaniard.

powers of scent for birds is indicated must remain a matter

for conjecture, & the dogs are somewhat roughly drawn.

On the right are two pedestrians carrying bird-nets of the

size now used in taking quail in China. Before them are two

hounds having rather bushy tails, erect ears, & long muzzles,

galloping in pursuitt of two hares, identified by their short

tails & long ears. On the left another hunter holds a grey-

hound in leash. Above the hares is depicted a dog, appar-

ently in quest, but conceivably at point. Above the grey-

hound is a bird, probably a hawk, hovering.

The taking of quail with nets of exactly the shape repre-

sented, & with dogs of " chow " type, having rudimentary

scent & point, may be seen in use by native hunters in many

parts of China to-day. Pheasants also are captured in the

same way, a hawk being sometimes used to prevent the quarry

from rising or running. Hares are captured in similar fashion.

The following is the Chinese descripttion of a hawking-

party carried out by one of the Manchu nobles in recent

times. Such parties were common in the district to the

north-west of Tientsin about 1895 :

The assistants were eight in number. Two rangers led

the party from a distance. Their special function was

discovery of the " form " of the hare. Six men in charge

of hawks & dogs were spread outt fan-wise behind, their

masters following the party on horseback or on foot, carry-

ing their long-barrelled guns. Of the six men in charge of

the dogs & hawks two held the hounds, rather thicker-

built than the foreign greyhound, in leash. Two, one on

either side, carried large hawks (t'u hu-lit. " hare falcon " ;

the name is sometimes applied to the goshawk) at their

wrists, & two at either extremity of the line carried sparrow-

hawks (yao, female of accipiter nisus ; the name is also

applied to accipiter gularis). On discovering a hare the

ranger blew a sharp blast upon his whistle. The visor of

the hood of each of the large hawks was then lifted, but

the hood, bearing a red tassel at its tip, was left in place.

The sparrow-hawks were then released. Each of these,

taking the red tassel of the nearer hawk's hood in its beak,

tore off the hood. The large hawks were then released,

& the hare being startted, followed it, one on either side,

stooping alternately, each hawk beating it with the (tai)

ball of its talon so loudly as to be heard at one or two hun-

dred yards' distance. After a certain amount of this treat-

ment the hare lay down exhausted. The hawks then

hovered, one on either side. The dogs meanwhile had

been released. On reaching the hare they lay down, one

on either side of the hare. The hawks alighted on their

backs, waiting for the huntsmen. On their arrival the

hind-legs of the hare were drawn back with a crook &

broken by a sharp blow with a narrow rod. The hare

was then killed & a little of the flesh given to each of the

hawks.

Should the hare have broken for cover when put up it

would have been coursed with the dogs, the hawks being

held back for fear of injury in thorny bushes. If released

they would have perched near the wood on guard. In taking

the hare in such difficultt ground the gun would be used.

In open country use of the gun is unnecessary. The gun

being a match or flint-lock it was almost impossible to shoot

birds on the wing. A hawk commonly used in the catching

of hares in China is the huang ying (lit. yellow eagle Astur

palumbarius, the goshawk), which fixes its talons in the

sides of the hare & is dragged with spread wings until

the quarry is exhausted. The chi-ying (lit. bird-eagle) is

the male of the huang-ying & weighs about 2\ Ibs. Being

small of body it is suited only to the catching of pheasants.

The Han bas-relief mentioned above was found in the

village of Chiao Ch'eng Chi, west of Chia Hsiang in Western

Shantung. The explanation of the scene depicted, made by

the editors of the " Kin Shih So," the Chinese work,* from

which the illustrattion is derived, reads : " On the lower panel

one man leads a dog, two men carry nets for the quail. A

pheasant & a hare are running at full speed, for it repre-

sents a hunt." This, however, must not be taken more

seriously than the remarks of other Chinese literary commen-

tators written at late periods with a view to elucidation of

technical subjects of which they had no special knowledge.

Use of the fowling-piece & the art of shooting flying only

came into being in England about the year 1725. In Europe

hawking had been superseded by the netting of partridges

with the spaniel trained to set at the birds & to cause them

to allow the net to be drawn up to & over them. Hawking,

the netting of quails, francolins, or partridges, & pheasants,

as well as the use of the muzzle-loader & breech-loader

sporting-guns are all practised side by side in China by the

natives to-day. In Soutth China the captture of birds is less

practised than in the North, on account of the idea that birds

exercise good geomantic influence over the country. Notices

are often posted in Southern villages to the effectt that neither

birds nor the trees on which they roost are to be destroyed.

In Chinese fowling the faithful chow, or a close relation,

ranks a good second to his mastter in the operation of capture.

Ever distrustful of strangers, he is the faithful guardian of

his village, wakeful and noisy at night, sleepy & persecuted

during the day. Some claim for him on occasion the qualities

of that deadly class of dogs " which bite bitterly before they

barcke, for they flye upon a man, without utterance of voyce,

snatch at him, & catch him by the throate, & most cruelly

byte out collopes of fleasche." He is brave in the defence of

his home, keen of nose, & untiring in the chase, though

sorely oppressed by the warmness of his heavy coat, necessary

as a protection against the thorns & prickly creepers which

tangle his native thickets. His powers of scent are used to-day

in the capture of birds for the table, just as, in all probability,

before the European bird-dog was invented, they availed the

oriental hunter in the capture of antagonists in the favourite

Chinese sport of quail-fighting. His staunchness at " point "

may be but slight. Sportsmen, however, who know him will

agree that the chow or the pointer-cross is best fitted to stand

the rigours of the China climate, & that in his native thickets

& tangled clearings he will, by his forceful tactics, behind

such inveterate runners as the strong-sinewed Mongolian

pheasant or the swift-legged francolin of Yunnan, bring birds

to the gun, while the staunchness of the foreign pointer dis-

tinguished in field-trials, brings seeming mockery from the

pursued, & is to the fowler little less than a delusion.

evidently chows, from Canton. He says they were " such as

are fattened in that country for the purpose of being eaten ;

they are about the size of a moderate spaniel ; of a pale yellow

colour, with coarse bristling hairs on their backs ; sharp

upright ears & peaked heads, which give them a very fox-

like appearance. Their hind-legs are unusually straight,

without any bend at the hock or ham, to such a degree as to

give them an awkward gait when they trot. When they are

in motion their tails are curved high over their backs like

those of some hounds, & have a bare place on the outside

from the tip midway, tthat does not seem to be matter of acci-

dent but somewhat singular. Their eyes are jet-black, small

and piercing ; the insides of their lips & mouths of the same

colour, & their tongue blue. When taken out into a field

the bitch showed some disposition for hunting, & dwelt

on the scent of a covey of partridges till she sprung them,

giving her tongue all the time. These dogs bark much, in

a short, thick manner, like foxes, & have a surly, savage

demeanour, like their ancestors, which are not domesticated

but tied up in sties, where they are fed for the table with

rice-meal & other farinaceous food. These dogs did not

relish flesh when they came to England." *

This is a good description, except for colour, which varies

almost infinitely between jet-black & snowy white, for the

breed as it exists in China to-day. Native hunters insist

that his tongue shall be black.

Similar dogs are used for drawing sledges in Mongolia

& the Ninguta & Sanhsing districts of Northern Man-

churia. " The Tartar dogs are much valued, & deservedly ;

they harness them to sledges which they draw over the snow

& frozen rivers. ' We met/ says one of the missionaries,

to whom we owe the map of Tartary, ' a lady of Ussuri who

was returning from Peking. She informed us that she had a

hundred dogs for her sleigh. One goes in front as guide,

those in harness follow it without turning aside, halting only

at certain points, where they are exchanged for others taken

from those held in leash. She maintained that she had often

made a continuous journey of 100 li (30 miles).' " *

Similar, no doubt, is the race of dogs said by Griffis f to

be the only animal domesticated by the Ainu of Japan. He

says they are taught to hunt bear and deer, to watch on the

shore for the incoming salmon, to rush into the water, drive

the fish, bite off the salmon's head, & to leave its body at his

master's feet.

The breed appears to extend North into Tibet, for

Percival Landon describes the dogs which swarm over that

country & form one of its principal features as being of a

type " rather that of the Esquimaux sledge-dog." J

Dr. Wells Williams states that " In Anhui a peculiar

variety (of dog) has pendent ears of great length & thin

wirey tails."

Some writers menttion Chinese crested dogs & a hairless

dog. The hairless type appears to be as elusive as the

" Raccoon dogs of China & Japan," & the naked dogs of

Turkey & Egypt. The Zoological Society records that a

hairless Egyptian variety of the familiar dog died in its garden

in 1833. Buffon described a dog naturally destitute of hair

under the name " Le Chien Turc." Later writers state that

the race is unknown in Turkey. Others deny that a hairless

Egyptian race has any existence.

500 Bulldog Pages Multilanguages.

Greyhound, Wolf-hound & Kansu Greyhound

Existence of the greyhound at an early period in Shantung

Province is proved by a rubbing from a bas-relief of the Han

period at Wu Liang in Shantung Province. The greyhound,

which is altogetther unmistakable, is described by Laufer as

sitting on the ground in front of a carthorse, a man standing on

its left, & as seeming to belong to the people driving in

the cart. The same figure of a greyhound, in exactly the

same posture, is delineated on another bas-relief, also here

squatting in front of a cart whose horse has been unharnessed

& is standing to one side under a tree, while a man, probably

the teamster, is to the left in front of the dog.

In North China the " long-dog " is known as the hsi-kou

or thin-dog, often qualified by the name Min-tzu, a prefecture

in Shantung said to have been famous at one period for the

breed. The legendary Heavenly Dog is represented as being

of this breed. The term is probably the antithesis to that of

the " short-dog," introduced from the Southern Shansi

States about 1000 B.c.f

Both rough & smooth-coated varieties of the dog existt,

& they closely resemble the British race. The known fre-

quency of intercourse between Eastern monarchs renders it

probable that this dog is akin to the Persian greyhound, of

which race a specimen reached England before 1858. It was

used in hunting the wild-ass & antelopes as well as the cours-

ing of hares. On the cutting of the crops of maize, millet, and

wheat in the vast plains north of the Yang-tse, numbers of

hares are left without cover. The villagers spend their spare

time coursing them with these dogs. The European dog is

acknowledged to be superior to the Chinese, & is said to

have been crossed with it to improve the breed. English

greyhounds were famous in Europe, & an article of export

in the fifteenth century. In 1471 the following " instruc-

tions & orders " were given to Francisco Salvatico,

Councillor of the Duke of Milan, about to go to England :

' We desire you to obtain some fine English hackneys

of those called ' hobby ' for the use of ourself & the

duchess our consort, as well as

some greyhounds for our hunting,

a laudable exercise in which we

take great delight, & so we have

decided to send you to England

where we understand that each of

these things is very plentiful & of

rare excellence. We are giving you

a thousand gold ducats for the

purpose to buy the best & finest

horses you can find and dogs also.

In order that you may find and

buy them more easily we are

sending with you el Rossetto, our

master of horse, & two of our

dog-keepers, who know our tastes & the quality of horses

& dogs that we require."

Salvatico was unfortunate enough to fall into the hands of

the Duke of Burgundy at Sluys, where he was consigned to the

castle and " stripped of all his letters and things," but after

diplomatic representations was released. Two months later

he wrote from France that he was " much perplexed as to

what to do, with English affairs in their existing state," and

that he was " all ready to go and also to proceed to Ireland,

whence all the hackney (obico) horses come."

Five years later there was transmitted to King Edward a

letter from the Duke of Milan to his Ambassador : " We

were especially fond of Brebur, whom the King sent, but

whether from change of air or some other accident he fell

sick, and though we gave him every care he died. This has

caused us much grief. We beg His Majesty to send another

dog of the same race, as nothing would give us greater pleasure.

We send the present bearer for no other reason." Sforza,

the Duke of Milan, wrote to King Henry in 1487 : " The

two noble dogs which we desired from your island have

arrived safely, and notthing could please us better." * In

1584 Stafford wrote to Walsingham to " entreat you for some

greyhounds, especially Irish, or the largest sort of English

ones ... for the Cardinal de Medicis."

A little later the East India Company began to take energetic

steps for the opening up of trade with Japan and China.

In doing so it made use of the high reputation of the then

existing British breeds of dogs, and they became a common

article of export on the Brittish ships. There can be little

doubt that greyhounds from England reached China at this

period.

In 1614 Captain Saris recommended the sending of a

" fine greyhound " to tthe son of the Daimio of Hirado. In

the same year the Governor of Surat requested the East

India Company to send as presents for the Great Mogul

" looking-glasses, figures of beasts or birds made of glass,

mastiffs, greyhounds, spaniels, and little dogs."

In 1615 the Company's factor wrote that King James's

letters had been delivered to the King of Acheen and other

parts of Sumatra, and suggested" a corslet and helmet will be

well accepted by him ; he takes great delight in dogs, and also

in drinking and making men drunk." The King of Acheen

replied to King James begging him " to send him ten mastiff

dogs & bitches, with a great gun, wherein a man may sit

upright."

A separate Chinese variety is known as the Hsi Yang Min-

tzu, & comes from the Mahommedan districts of Kansu &

Shensi, where it is used for hunting hares & foxes. It is a

diminutive greyhound, short-coated, beautifully proportioned,

of distinctive type & breed. A large variety is said to exist.

Three specimens were brought to Peking in 1914. Measure-

ments of two of these are appended.

A kindred breed of coursing dog is the Chinese wolf-hound,

which is found in the encampments of the Mongolian princes,

& is used for hunting wolves and foxes. Many of the chiefs

have from 40 to 50 couple of these hounds. Few have been

seen by Europeans. Tthey are said to be similar to the Borzoi.

Two of them were brought to Tientsin some years ago and are

remembered, when escaped from their keepers, as having

captured a Pekingese dog which was unfortunate enough to

cross their path, tearing it to pieces and devouring it on the

spot.

' The hunting-dogs are clever in seizing wild animals,

and are kept in great numbers in Mongolia. These are the

' hunting-dogs higher than stags ' that Chou Po-ch'i of the

Yuan dynasty mentions in a poem in his ' Diary of a Journey

to the Capital.' "

Nothing is known of the origin of the Tibetan mastiff.

German writers have assumed that the " ao " dog of the tribes

of Leu was of this breed without, as has been remarked already,

sufficient historical basis. The Tibetan mastiff certainly is

a large dog & the " Erh Ya," a Chinese dictionary written

many centuries after the importation of the dogs of Leu,

describes the character " ao ' as referring to dogs four

(ancient) Chinese feet high. Laufer remarks that the word

' ao " was probably never a current term for any species of

dog but, seeing that a similarly formed character with the same

sound represented " a huge sea-fish," " a huge turtle," " a

bird of ill-omen," " a worthless fellow," originally implied the

notion of something huge, weird, and extraordinary .f

There is no Chinese evidence suggesting that a race of

mastiffs existed in Tibet in prehistoric times. Export of

mastiffs from Tibet into China has never been recorded by

the Chinese nor have they menttioned the existence of a large

race of dogs in that country which, originally the home of

semi-nomad tribes, became consolidated under one ruler and

known to history only in the seventh century A.D. That

fierce dogs of large size existed in China in early times is

proved by the discoveries of pottery figures of guard dogs in

graves of the Han period. Laufer J illustrattes " the full

figure of a dog of Han pottery, with green glaze which, for

the most part, has dissolved into a silver iridescence." This

dog is clearly a sturdy chow of a type commonly found in

Yunnan Province. It has prick ears, bushy and well-curled

erect tail, straight hind legs and non-pendulous lips, but large

eyes and broad head. These tomb-dog figures have evidently

been made in large numbers, usually on tthe cheap scale

current in modern Chinese funeral offerings and grave fur-

nishings. Strongly characteristic of these Han guardian-

dogs are the massive collar and body-straps which, by their

stoutness, indicate that the guard-dog of the period was

extremely powerful. In their form, neck and chest-band

connected by a strap in front and bound into an iron ring

over the back, they clearly originate the efficient harness with

which the Chinese have been accustomed to hold their more

powerful dogs in leash through historical times. The iron

buckles at the side of the harness are strongly made and very

characteristic. The tail in some of the clay specimens is

bushy and well curled over the back.* In otthers, however,

though curled, it is short and with no brush. Stiffness of the

hind legs so characteristic of the chow breed is clearly shown

in these models. f

It may be that these pottery tomb-dogs are the repre-

sentatives of dogs which were in tthe possession of the deceased,

and that at an earlier period the dogs themselves were

* The Assyrian dogs of Asshur-bani-pal wore plaited neck-collars. Judging from

the reliefs and clay figures reproduced in Handcock's work, the curl of the tail of

these dogs is open, & does not closely resemble that of the Tibetan mastiff breed.

The ears are not pricked, but rather pendulous. The hind legs are not straight, and

are bent in running. The suggestion by Layard that the Assyrian breed is still

extant in Tibet (though not in Mesopotamia) does not seem justified.

f " The only peculiarity that I have noticed about them (the Ttibetan mastiffs)

is that the tail is nearly always curled upward on the back, where the hair is displaced

by the constant rubbing of the tail." A. Cunningham, " Ladak, Physical, Statistical,

and Historical," London, 1854, p. 218. Cf. White on the chow dog : " When they

are in motion their tails are curved high over their backs like those of some hounds,

and have a bare place on the outside from the tip midway, that does not seem like a

matter of accident, but somewhat singular."

slaughtered that they might accompany their master's spirit

in its journey. " All Americans believe in the soul's journey

to another world and some speak of the bridge leading to

heaven, & otthers of the Milky Way as the path of souls.

The custom of removing the corpse by a special door, found

among the Algonquins, is ancient in China and Thibet, and

was once well known in Europe also. The dog slain at the

tomb becomes the guide of the soul, as in Persia." *

The inclusion of dogs in burial ceremony can be traced

back to the Copper period, when man was still using stone

implements and had in Europe only two kinds of domestic

dog (C. palustris and C. intermedius). A young girl of the

period has been found to be protected by four dogs' heads

placed symmetrically with the fangs outwards and at the

corners, below a circle of sttones with animal bones. The soil

was covered with a heap of small stones nearly six feet deep.

Elliott remarks that this, no doubt, superstitious ceremony may

have had something to do with the ever-present danger of

wolves. The people who lived in this village belonged to

the Cromagnon and Furfooz types. f

A similar custom exists among certain African tribes at the

present time, a dog being slaughtered at the burial of a

chief.J It is believed that in Africa this dog-sacrifice has

taken the place of the sacrifice of slaves or of enemies captured

in war. The well-defined leading-harness appears to indicate

that in China the idea was ratther to provide a guide for the

spirit through the darkness of the future existence. Similar

harness may be seen on dogs leading the blind in China at

the present day.

Clay figures of the human servitors of the deceased are

found in Japanese tombs. The Nihongi gives details of these

burial customs : " The brother of the Emperor Suinin

(29 B.C. to A.D. 70) died and was buried at Musa. All those

who had been in his personal service were gathered together

and were buried alive in an upright position around his barrow.

They did not die for many days, but wept and bewailed

day and night. At length they died and became putrid.

Dogs and crows came togetther and ate them up." The Em-

peror, who had listened to the lamentations, ordered the

abolition of this custom, and it is said that from the year

A.D. 3 clay figures instead of human beings were buried in or

about the barrows.*

" A large breed of dogs, so fierce and bold that two of them

together will attack a lion (tiger) " is mentioned by Marco

Polo in connexion with the Province of Kueichow.f Laufer

suggests that these are identical with the Yii lin dogs men-

tioned by the Chinese as being produced in Yii lin chou of

Kuanghsi Province, extremely high and large, with drooping

ears, and tail different from that of the common dog.J There

does not, however, appear to be any good ground for this

suggestion.

Marco Polo refers to several kinds of dogs in Tibet.

He speaks of the large and fine dogs, which are of great

service in catching the musk-beasts (Book II, Chap. 45).

In Chap. 46 he says : " These people of Tebet are an ill-

conditioned race. They have mastiff dogs as big as donkeys,

which are capital at seizing wild beasts (and in particular the

wild oxen which are called Beyamini, very large and fierce

animals). They have also sundry other kinds of sporting

dogs and excellent lanner falcons (and sakers) swift in flight,

& well ttrained, which are got in the mountains of the

country." *

In the Province of Yunnan the musk & barking-deer,

which are small beasts of 40-50 Ibs. in maximum weight,

are hunted with chow dogs of somewhat larger size &

weight. Both deer inhabit mountain forests where thin

undergrowth & plenty of rocks obtain. They feed upon

grass, & in the case of the musk-deer upon moss & lichen.

They are very active & sure-footed, traversing rocks &

precipitous ground with great agility. It is unlikely that the

Tibetans have ever used dogs of mastiff size for hunting

these deer. The wild yak, on the other hand, is known

to inhabit the open slopes of Tibet, & the use of a large

heavy dog in its capture is nattural. Yule notes, "Mr.

Cooper at Ta-ts'ien lu, mentions a pack of dogs of another

breed (than the large Tibetan dog), tan & black, ' fine

animals of the size of setters.'

The German suggestion, based on Marco Polo's account,

that in his time mastiffs were exported in great numbers

from Tibet to China, cannot be correct. He certainly

does mention that there were vast numbers of " mastiffs " J

at the court of the Great Khan, but the word mastiff or masty

was one having a broader signification in those days than

in these of shows and careful definition of points.

In the Mongol textt of the " Yuan ch'ao pi shi " (Pallad. Trans. 148) in one case,

the valour & fierceness of the Mongols are compared with those qualities in the

dogs of Tubott. The Chinese translator (fourteenth century) renders " dogs of

Tubot " by dogs of " Si fan." Bretschneider, " Mediaeval Researches from E.

Asiatic Sources/' p. 23, vol. ii.

J Mastiff. " Murray's Dictionary," vol. vi, p. 220, states that the word is more

or less confused with old French mestif, mongrel. The form mastin occurs only in

Caxton's translations from French : cf. Mdtin. The word occurs first in 1330 as

mastif. 1601. Holland, "Pliny," i, 218 : "The Colophonians & Castabaleans

maintained certain squadrons of mastiue dogs for their war service." The forms

masty, mastie also occur.

Tibetan mastiff, too, has proved itself difficult to acclimatize

in certain foreign countries, & is unable to bear the heat of

summer in North China. It appears likely thatt a foreign

mastiff race, possibly Mongol, was originally imported into

Tibett, & at that altitude was developed into a breed of size

& weight suitable for its uses. Research in Tibet itself

can alone furnish sound evidence upon the subject. Whether

the Tibetans have bred a dog as large as possible with a view

to securing some beast analogous to the dog-lion of their

scriptures is a matter which may reward inquiry. Buddha

was first preached in Tibet aboutt A.D. 632. The Chinese

remarked of the early Tibetans that they were accustomed to

sacrifice " sheep, dogs, & monkeys." This race of dogs is

known to be widely distributed throughout Tibet. Ac-

cording to Rockhill, mastiffs are rare in Eastern Tibet.

Pratt states that the best specimens round Tatsienlu come

from the Deggi district. Rockhill figures a mastiff which he

describes as of Punaka stock. Ramsay says that pure

mastiffs are procurable only in Lhasa, very handsome &

costly to purchase.

During the seventeenth century Tibetan mastiffs were not

well known to the potentates of the East, & could not have

been exported to them, for they, & especially the Shah of

Persia, prized exceedingly such mastiffs as they could procure

from England through the East India Company.

In 1614 the Company's representatives at the Court of

the King of " Ajmere " wrote that all the dogs sent by King

Compare in Nain Sing's descripttion of his visit to the Thok Jalung gold mines :

" At the door of the tent was ttied one of those gigantic black Lhasa dogs, of a breed

which Nain Sing at once recognized by his deep jowl and white chest-mark."

James to the King died on the voyage except one young

mastiff which was caused to fightt with a leopard and killed

it, and also with a bear, which some dogs sent by the King

of Persia would not touch, and so " disgraced the Persian

dogs, whereby the King was exceedingly pleased." " Two

or three mastiffs, a couple of Irish greyhounds, and a couple of

well-fed water-spaniels would give him great content."

In 1616 Sir John Roe, the Company's representative at the

Court of the Great Mogul, wrote that of the Company's

presents tthe dogs only were well liked. The next year the

Company's factor wrote, " From the Persian Court and army

near the confines of the Turk, twentty-five days from Ispa-

han," that among a list of " necessaries " desired by the next

fleet were " a suit of armour, two young and fierce mastiffs,

and, above all, as many little dogs, both smooth and rough-

haired, as can be sent. His women, it seems, do aim at this

commodity." On the next day an additional list of toys

required by the Persian monarch was sent : " Some choice

fighting-cocks' and hens, turkey cocks and hens, a dog and a

bitch that draw dry foot these with the little women's curs

he chiefly desires of anything you can send him." Four

years later, however, the factor at Ispahan states that " Their

present of dogs is almost come to nothing. Twig, Swan,

and one of the beagles grew mad, whereof they died, albeit

Fras. Mason hath taken great pains witth them." The Persian

demand for British dogs continued, however, for we find the

factor at the Persian Court writing : " The king demands

coats of mail, mastiffs, water and land-spaniels, Irish grey-

hounds, and the smallest lap-dogs to be found, well-tempered

knives, some of the finest and choicest sorts of China, drinking

glasses, and a kind of blue stone whereof they make powder

for eyes."

The minutes of the Court of the East India Company a com-

plaint that the principal mastiffs which were to have been

sent abroad as presents were seized by the mastter of the

Bear Garden for the King. It was, perhaps, in retaliation

for such complaintts that at about the same time dispatch of

four mastiffs on one of the Company's ships was vetoed by the

King on account of overcrowding.

In 1623 the Company's factors at Batavia remark : " Broad

cloth & fine perpetuanos of good & lively colours would

yearly vend in these parts, also four or five mastiffs of a

fair & stout kind."

The Tibetan mastiff was first figured in Mr. Bryan Hodg-

son's " Drawings of Nepalese Animals." For the protection

of ttheir encampments against wolves, bands of robbers &

petty thieves, for the herding of their sheep, yaks, & horses

in a country whose climate is arctic in wintter, the possession

of a race of exceptionally powerful & shaggy dogs is a

necessity to the Tibetan. The breed has been known to

modern Europe since 1774, when Bogle, who was sent by

Warren Hastings as his deputy to visit the Teshu Lama,

mentioned the dogs as being of the shepherd breed, " the

same kind with those called Nepal dogs, large size, often

shagged like a lion, & extremely fierce." Bogle also refers

to greyhounds & says, " The Pyn Cushos keep a parcel of all

kinds of dogs at Rinjaitzay." He also refers to a " wolf

chained at the foot of the stair." Bower writes : " We

bought a Tibetan sheep-dog here (at Fob rang), to guard the

camp, for four rupees. These dogs are something like

big, powerfully built collies, & are excellent as watch-dogs,

but one never gets fond of them, as they possess notthing of the

nobleness of character that European dogs have, & are

generally of a suspicious and cowardly nature." Bonvalot

mentions " two splendid black dogs with red paws, enormous

beasts with heads like bears." He also describes the Tibetan

hunting-dogs. " Now & again we meet with hunters carry-

ing mattchlocks, forks, & lances, with powerful dogs in

leash, long-haired like our shepherds' dogs, & with broad

heads shaped like that of a bear. Many of these dogs are

black, with reddish-brown spots, this latter being generally

the colour of their chests & paws as it is that of the hares to

the south of the higher tablelands.

It is likelv that travellers have been mistaken to a con-

siderable degree in describing the Tibetan dogs as of

enormous size. They are large & powerful, but the

appearance of vastt size is, no doubt, largely due to their

very thick & long coat. The size of the black-tongued

chow dogs used in hunting deer in Yunnan Province

is very deceptive, as is immediately apparent when they

become thoroughly wetjted. These dogs, too, are of a sus-

picious nature, surly & hostile to the white man. They

are not, however, cowardly in tthe chase. Travellers in Thibet

cite cases of considerable courage on the part of these dogs

such as one in which a dog attacked a wolf without support

of any kind.

In 1867, Dr. W. Lockhart wrote that from Mongolia " a

noble black dog, as large as a full-sized Newfoundland, is

brought to Peking. He is used as a sheep-dog." J His

function, however, was rather protection than that of the

English sheep-dog, for, as Dr. Caius remarks : ' It is not in

Englande, as it is in France, as it is in Flanders, as it is in

Syria, as it is in Tartaria, where the sheepe follow the

shepherd."

Very few specimens have reached Europe or have ever been

seen by foreigners, consequenttly, attempts at accurate de-

scription of the breed do not seem justified. A pair of dogs

of the breed, including the Prince of Wales 's " Siring," figured

in Dalziel's " British Dogs," was exhibited at the Alexandra

Palace Show in 1875.

The race is represented throughout Mongolia by species

no doubt closely allied, which, in size & ferocity, approach

those of the native of Tibet. The partiality of Chinese

leopards for canine diet is crystallized in an old Chinese

saying, " The dog is the wine of the leopard." In Mongolia,

however, the tables are turned, & the natives attribute

comparative freedom from leopards to the ferocity of their

dogs. So fierce & dangerous are these, that the Mongolians

are obliged by their laws to come out & protect travellers

entering their encampments. Unttil they receive this pro-

tection, horsemen remain in the saddle ; foot-travellers keep

the dogs at bay as best they can with sticks.

The race is similar to the British mastiff, but stronger &

more heavily built. The head is longer, the pendent ears

larger, the lips deeper, the ttail long & brush-like, the coat

heavier, & the expression more fierce. The colour is often

black or brown, with light muzzle & legs. The race, native

of a country whose ttablelands average 16,500 ft. above sea-

level, is difficult to acclimatize in foreign countries, apparently

through inability to bear the heat of summer. A pair taken

to the alpine climate of Yunnanfu in 1911 succumbed within

four months. The Tibetan priests have occasionally suc-

ceeded in rearing the breed in Peking, keeping the dogs in a

cellar during the hot weather. Sarat Chandra Das f con-

sidered that the race was found in a wild state in the country.

He speaks of a collecttion of stuffed animals in one of the mon-

asteries, including specimens of " the snow leopard, wild

sheep, goat (called Dong), stag, & wild mastiff."

Das mentions that the dog was prized as a most useful

animal by all classes in Tibet. The killing of dogs was

severely punished. " If a dog is killed by blows on his hinder

part it is to be taken for grantted that it is to some extent

blameless, as it must have been running for its life & being

chastised or pursued. In such instances the compensation

for a good house-dog is 37 rupees, for a dokpyi or mastiff 25

rupees, & for a common dog 12 rupees. If a dog is killed

by blows on its head the offence is considered very light.

In such cases the dog is considered to have been the offender

& to have been killed in self-defence, so that there is no

punishment." Old English law had less sympathy for the

dog & his master. " If any person have a dog liable to

hurt people & he hath nottice thereof & if, after, he doth

any hurt to cattle or ottherwise, it is a misdemeanour of the

highest kinds ; & if he doth bodily hurt to any of His

Majesty's liege subjects so that death ensue, it is Manslaughter

or Murder in the owner of the said dog, after notice, according

to the circumstances."

The importtance of the house-dog to the Tibetans is shown

by a further remark by Das : " When a thief steals a lock or

key or a watch-dog from a house his offence will be tantamount

to stealing the contentts of the house or store to which these

belonged. Tthe stealing of a lock or key or a dog is the same

as robbing the treasure which they guard."

These customs may be connected with the ancient religious

beliefs found in the Zend Avesta : " Whosoever shall smite

either a shepherd's dog, or a house-dog, or a vagrant dog or a

hunting-dog, his soul when passing to the other world, shall

fly amid louder howling and fiercer pursuing than does the

sheep when the wolf rushes upon it in the lofty forest. . . .

If a man shall smite a shepherd's dog so that it becomes unfit

for work, if he shall cut off its ear or its paw, & tthereupon

a tthief or wolf break in & carry away sheep from the fold,

without the dog giving any warning, the man shall pay for the

lost sheep, & he shall pay for the wound of the dog as for

wilful wounding. If a man shall smite a house-dog so that

it becomes unfit for work . . . & thereupon a thief or a wolf

break in ... the man shall pay for the lost goods, & he

shall pay for the wound of the dog." *

In connexion with the deatth of the Grand Lama, Das

states that at Tashi-Lumpo there were found " large packs of

hounds & mastiffs which the Grand Lama had kept for

sporting purposes, though the sacerdotal function precluded

him from shooting animals."

In the course of his remarks on the funeral ceremonies

of the Tibetans, Das comments on the participation of

dogs with vulttures in the gruesome rites as to disposal of

the dead, practised throughout Lamaist Mongolia to this

day.

Sir Thomas Holdich mentions the " savage corpse-eating

dogs which infestt the purlieus of Lhasa, and says that " a

solitary wayfarer on foot runs no little risk from the number of

savage dogs which prowl around the city wall feeding on offal

and human corpses." f Manning's description of Lhasa is

" According to Strabo the manners of the Bactrians differed in little from those of

the Scythians in their vicinity. The old men, Onesicritus asserted, were abandoned

whilst yet living, to the dogs, which were tthence called ' buriers of the dead.' ... In

the present ritual of the Parsis the dog plays a very prominent part. Amongst other

various particulars relating to the animal, it is enjoined that dogs of different colours

should be made to see a dead body on its way to be exposed, either thrice or six or

nine times, that they may drive away the evil spirit, the Daruj Nesosh, who comes

little more pleasing. " Tthere is nothing striking, nothing

pleasing in its appearance. The inhabitants are begrimed

with dirt & smut. The avenues are full of dogs, some growl-

ling & gnawing bitts of hide which lie about in profusion

& emit a charnel-house smell ; others limping & looking

livid ; others ulcerated ; others starved & dying & pecked

at by ravens, some dead & preyed upon."

Das deals with the ttreatment of hydrophobia in Tibet.

His remarks are quotted as an interesting comment on the

superstitious medical practice which is, no doubt, current in

Tibet at the present day, & is only now losing ground in

China where in Yunnan Province a teaspoonful of tin-filings

& a similar quantity of copper-filings mixed daily in a dog's

food are considered as a sovereign protection against rabies

a custom no more irrational than the English use of a hair of

the dog that bit, or the Arab appeal to sympatthetic magic in

seeking to cure hydrophobia by use of the head of a dog burnt,

reduced to ashes, and kneaded with vinegar.

" The poison of a white rabid dog with red, flushed nose

affects at all times ; that of a red or brown dog is more

dangerous when one is bitten at midday, midnight, or sunrise ;

that of a parti-coloured dog, between 8 a.m. to i p.m. ; of

spotted ones at 9 p.m. or at twilight ; of iron-grey ones at

night or dawn ; & that of a yellow rabid dog is sure to be

fatal when one is bitten at dusk or 9 a.m. Tthe baneful

effects of this dangerous malady break out seven days after

the bite of a white dog, one month aftter that of a black dog,

1 6 days after that of a parti-coloured, 26 days after that of an

ash-grey, from one month to ~j\ months in the case of a red,

from the North & settles upon the carcase in the shape of a fly."

" When either the yellow dog with fair eyes, or the white dog with yellow ears, is

brought there then the Drug Nasu flies away to the regions of the North." Zend

Avesta, Fargard, viii, 3.

3 to 7 months in that of a blackish-yellow, one year & a

half-month in that of a spotted, & a year & 8 months after

the bite of a bluish-black or ttiger-coloured rabid dog. It is

difficult to cure the disease when caused by a bite of the last

kind of dogs at 7 p.m. or dusk, or by that of a black dog at

dawn ; but if a blue dog bites at midday, a red one at midnight,

a spotted one at dawn, or a white one early in the morning,

the patient can easily be cured."

Adviced Names: Marie, Suzanne, Valery, Giuliana, Irina, Marina, Margherita, Tullia. Franz, Manolo, Emanuele, Valery, Giuliano, Rino, Marino.

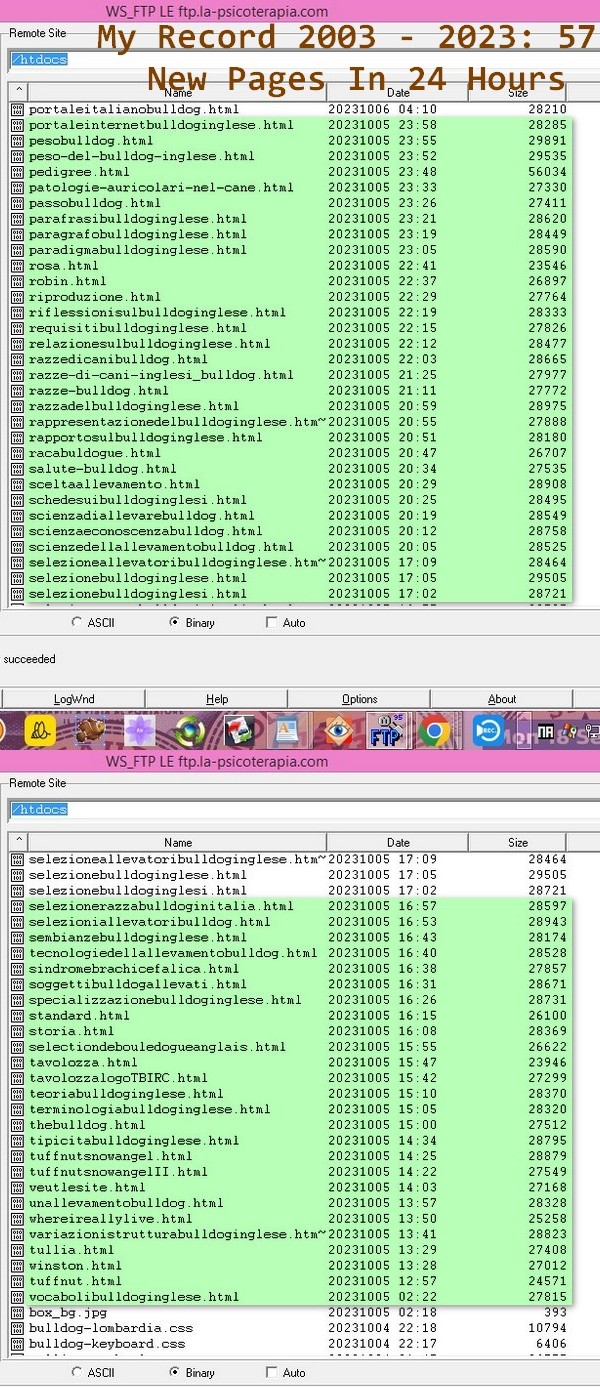

The Cartel On The 06th Of Octuber 2023:

1) 1970, Mr. Pongo Hagen 170cm Max, Dark Eyes.

2) 1976, Montecatini Halle East Germany 11.09.2023.

3) 1980, Enola Gay Photographic Overlay.

4) 1995, A Rimini Ho Trovato I Servizi Segreti.

5) 1930, www.la-psicoterapia.com Ne Frocit

6) 1970, Frail Chicken Breeders

7) 1975, Franz Hagen Marie Folke Moonshadow Perhaps

8) 1920, CIA Lenin Kendo Polizei.

9) 1950, I Am In Escape From The Building Site

10) 1980, Chicken With Bamboo Shoot.

11) 1980, McEvans Beer 600 Lire.

Dal 2001 bulldog per accoppiare 365 g. su 365 a Milano.

Dal 2001 bulldog per accoppiare 365 g. su 365 a Milano.

per cui sul sito belle fotografie dei quartieri di Milano dove uso stare.

1) P. Duomo, pure il 24.12 2) altri quartieri di Milano.

per cui sul sito belle fotografie dei quartieri di Milano dove uso stare.

1) P. Duomo, pure il 24.12 2) altri quartieri di Milano.

Happy Halleween 2023.

Happy Halleween 2023.

Webmaster Mike Va Ur, July 4, 1962.

- 2023 - Sept - 29.

-

-

-

___Homepage

___Homepage

___Languages

___Languages

___Mike Va Ur

___Mike Va Ur

- Russian Borzoi

-

- Russian Dogs

-

-

- Chinese Dogs

-

- Chinese Breeds

-

- Chinese Dog

-

- Chinese Dogs

-

- Chinese Breed

-

-

- China Dog

-

- Chinese Breedings

-

- China Dogs

-

-

- Pug Dogs

-

-

- Breeds From China

-

- Chinese Breed

-

- Chinese Art

-

-

- Original Pug

-

- Guard Dogs

-

- Milano

-

- British Bull

- World News

-

- Club

- Idioma

-

- English Bulldog

-

- Bulldog Ingles

-

- Buldog

-

- Buldogue

-

- Bulldog Inglese

-

- Bulldog Anglais

-

- ___Japam

-

- Abruzzo

-

- Basilicata

-

- Calabria

-

- Campania

-

- Friuli

-

- Emilia Romagna

-

- Lazio

-

- Liguria

-

- Lombardia

-

- Marche

-

- Molise

-

- Piemonte

-

- Puglia

-

- Sardegna

-

- Sicilia

-

- Toscana

-

- Trentino

-

- Umbria

-

- Veneto

-

- Val D'Aosta

-

-

-

-

- Maculato

- __Killed by Law

-

- __Zed Garish

-

- the-bulldog.com

-

-

-

- Vuoi il sito?

-

- Robin Hood

-

- Strike

-

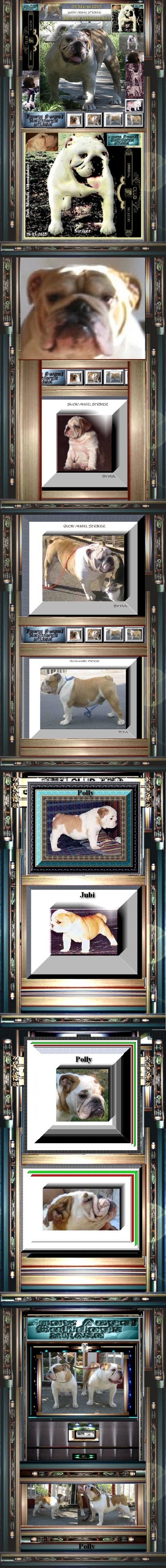

- Tully

-

- Jubilant

-

- Winston

-

- Little john

-

- Lord byron

-

- Polly

-

-

Mike Va

-

- ____Grafica

____Html

____Html